To Challenge A System

As some may know, I’ve used a still of Elliott Gould in THE LONG GOODBYE as my social media avatar for a long time. It was only within the past year or so that I finally substituted an actual photo of myself on my Facebook page but that’s semi-private anyway and it may as well be clear to people I went to high school with that it’s really me. But the Gould photos have stayed up in those other places and by this point it would just feel strange to get rid of them. Despite this, or maybe because of this, I’ve never tried to meet the man when he’s appeared at screenings or those times when I’ve randomly spotted him out in the world. It just feels like it would be a little too weird. Then last summer I was standing outside the New Beverly after a double bill on a night when Elliott Gould happened to be in the audience. As he was being helped to his car someone who presumably knew who I was said, “Elliott, you have to meet Peter! He’s one of your biggest fans!” and there was nothing I could do. Incidentally, this was not after a night of Elliott Gould films, he was just there to see MAN ON THE MOON with screenwriters Larry Karaszewski and Scott Alexander there to talk about it followed by Milos Forman’s brilliant 1970 satire TAKING OFF. But back to Elliott Gould, there was nothing I could do right then so of course I got to meet him and of course I told him how much I loved his work. I even briefly mentioned that I had taken my girlfriend to see CALIFORNIA SPLIT the night of our first date so he had played a small part in things but there wasn’t much time for all this to have any real effect. My point is that after so many years I finally had a brief, oddly memorable, moment with the man.

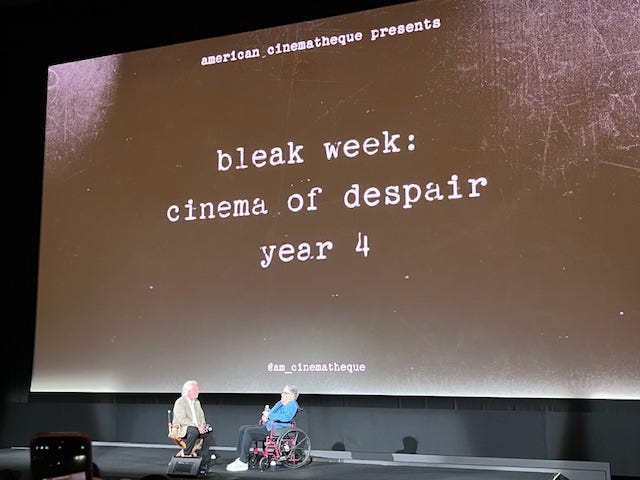

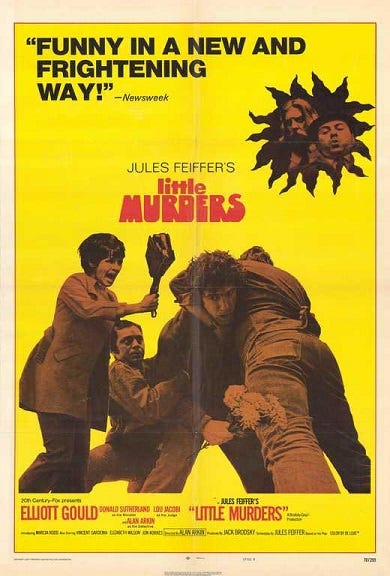

Cut to almost a year later this past June and I was at the Egyptian for opening night of the American Cinematheque’s Bleak Week with a showing of the 1971 satire LITTLE MURDERS in 35mm featuring Elliott Gould, the film’s star, in attendance. Of course I had to be there. It felt important to be in his presence right now and this seemed like the right sort of film for it to happen. I wrote about LITTLE MURDERS after first seeing it a long time ago so it’s interesting to compare that to how I feel after all these years. Not just about the movie but about everything. LITTLE MURDERS encourages that kind of thinking. However I felt about it then, what sticks out now is how much the film has seemingly become about this very moment we’re living in, as if the moment it was created has somehow circled back and because of that what the film has to say about it all means even more. Sometimes it’s not easy to know how much we should care anymore about things and that’s a question we get confronted with as things seem like they’re getting worse. So, of course, right now this film makes perfect sense.

Originating as a play written by Jules Feiffer in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination when the writer felt like the country was undergoing a collective nervous breakdown, it’s hard not to think that by the time the film, directed by Alan Arkin, came out several years later as the ‘60s turned into the ‘70s it felt even more of the moment. Maybe it’s even more of the moment right now. Of course, things are strange these days. On a personal level, certain things are very good and maybe better than they’ve been in a long time but then there’s the world around us. You don’t need me to tell you. Feiffer’s inspiration for writing the play is the sort of thing that makes the film version of LITTLE MURDERS likely play better now than it has in decades. It’s a little depressing to think that no one is going to make a movie like this which examines things right now in this sort of way but, in fairness, no one knows what form that breakdown will be taking once another year has passed. But we still have LITTLE MURDERS, to tell us what that feeling of someone understanding the moment can be like.

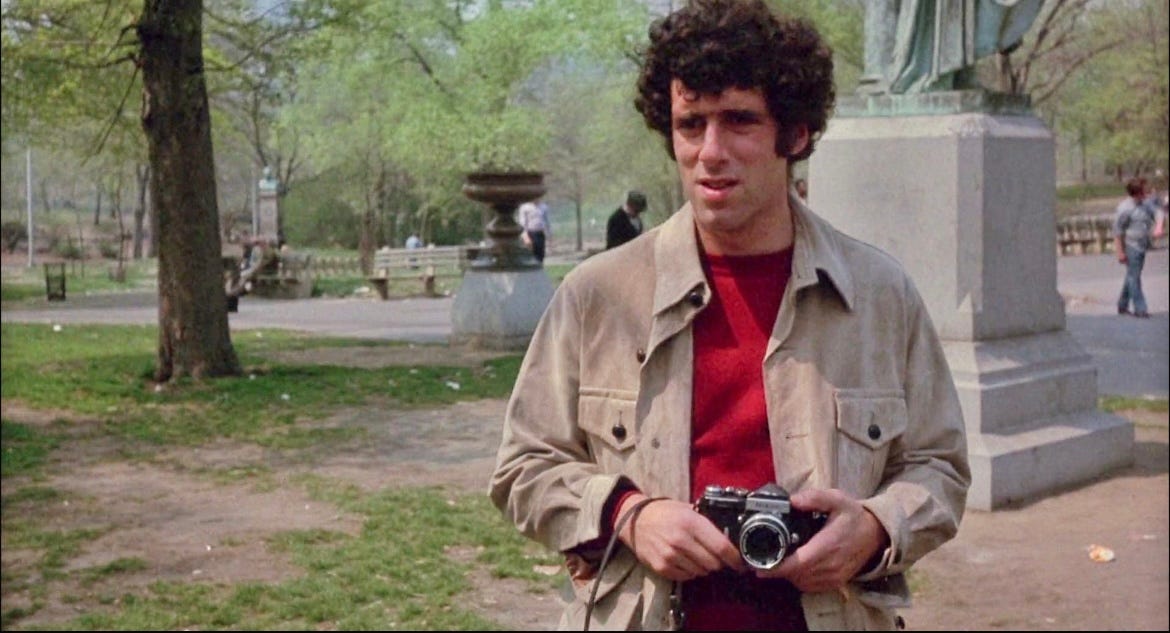

Alfred Chamberlin (Elliott Gould) is a photographer getting beat up on the street one day when he meets Patsy Newquist (Marcia Rodd) who tries to help him but when the people doing this go after her he simply walks off. When she finally gets the chance to berate him for his cowardice she instead ends up drawn to him, fascinated by his completely apathetic view of life, willing to get beaten up as long as they don’t touch his camera since they’ll get bored and stop eventually. Patsy becomes determined to get Alfred to love her and he’s the latest in a string of men she’s tried to mold. After bringing him home to meet her mother (Elizabeth Wilson), father (Vincent Gardenia) and brother Kenny (Jon Korkes) she gets him to agree to marry her, leading to confrontations with a judge (Lou Jacobi), the reverend (Donald Sutherland) who agrees to perform the ceremony which further leads to Alfred trying to find out about his past from his parents and somehow feel something in a world where feeling anything seems to be an introduction to pain.

Tone is always a very important thing when it comes to making a film and it can be one of the easiest things to botch, particularly when it’s a deadly serious satire where the laughs can’t simply be regular movie laughs. Not to mention how this sort of absurdism that can seem totally at home in a grimy, tiny off-Broadway theater can suddenly play completely flat when presented in the harsher reality of a film, set in that 1970 New York where it really does seem dangerous out there on the street and photographed by Gordon Willis, the DP who seemed to understand the city like no other ever has. This was the great Alan Arkin’s first film as a director (I’ve never seen his second and last, 1977’s FIRE SALE, and these days it doesn’t seem like many have) which displays such a confidence of tone as well as an understanding of how to approach these ideas that it feels like a total fusion with the material that makes it clear everyone involved was on the same page. With Jules Feiffer adapting his own script for the screen, there are lengthy stretches where the material seems to come directly from the stage but it always feels cinematic in its own particular way with a stark absurdism that could have easily fallen flat but is brilliantly directed by Arkin with this version of reality that’s being presented becoming hysterical and terrifying all at once. The film always knows to be both things, never just one or the other. And it always knows where those laughs need to be.

The film begins with Patsy and she’s the one person who seems to notice the way everything really is as well as the one who wants to fight back by not losing her humanity. This seems to extend to her knack for wanting the save the men she meets and once she spends a few minutes with Alfred that’s it, no matter what he has to say about it, no matter how much he insists that he doesn’t know what love is. “I don’t want to hurt you. I want to change you,” is what she tells him, practically smothering this man she’s just met as she tried to mold him into this ideal man she knows is there. The apathetic way of living that the main character goes through, he doesn’t even care about fighting, makes it perfect. She tells him how much she wants to keep smiling and find that good in the world, she wants to feel those feelings, she wants him to see that they’re worth feeling. He can’t. This leads to meeting her family, a very specific dynamic which becomes the center of the film and the rhythm of it all becomes a beautiful thing with expert timing from the actors that lets them find the words making it all sound genuine no matter how absurd it gets. As Alfred talks about his photographing actual shit for a living, the very word horrifies the mother played by Elizabeth Wilson who is still trying to keep up appearances and pretend that everything is still normal, recalling the things her own mother did as if she still lives in a world where such traditions matter. Getting married to Patsy leads Alfred back to his own parents who welcome him with blank politeness and have no idea what to say to him, approaching everything about life with pure intellectualism coming from what they’ve read, offering up the phrase ‘the dynamism of apathy,’ which seems to be a way of life that he’s been formed by and leaves him with no answers at all.

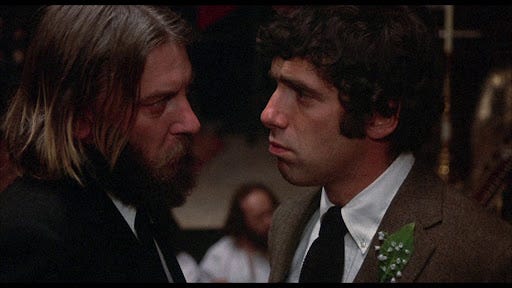

It's all a portrait of what society has become, whether it’s the heavy breather constantly calling Patsy wherever she is, the violence that everyone seems to accept as natural or Patsy’s old boyfriends still doing whatever they can to stick around. When her brother casually states, “What I really want to do is direct films,” as just one more drop of insane things that people say it feels like a joke that especially caught in the throat of a lot of people at the Egyptian that night. The people who are meant to represent the versions of authority only add to all that madness whether the judge played by Lou Jacobi bellowing to the sky along with Arkin’s own fearlessness in his appearance as the much talked about Lieutenant Practice. But the one really remarkable sequence, maybe the best scene in the whole film, has Donald Sutherland turning up for one scene with his MASH co-star as the reverend marrying Alfred and Patsy given a tour de force soliloquy which is remarkable with language brought to all this by Feiffer is undeniable but what Sutherland brings to it is an uncanny observation of all this language that finds the laughs in every single place along with an insistence on this form of truth trying to address how much ever makes any sense at all.

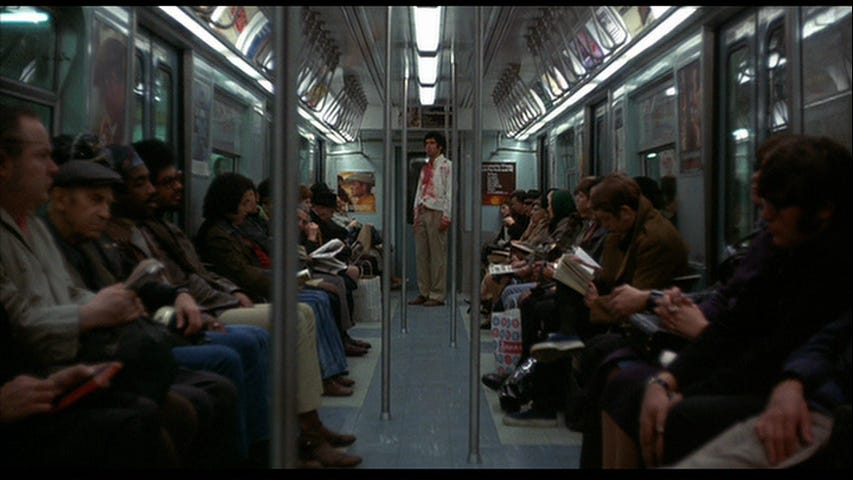

I’m old enough now that certain feelings do come through. Some of what I’m going through right now even fights against how much I respond to this film. Cynicism feels unavoidable, no matter what I want to think. I want that sense of feeling and kindness and love, I want that life with the person I now know but the other stuff is still there and there are times when everything combined makes absolutely no sense. I just need to keep fighting through it all and find the good. Maybe I have to do that more than anything. I wasn’t around yet in 1970 but something about the version of it presented in this film, as exaggerated as it might be, feels like what I imagine it was for the laughs to be as frightening as they are. The shot of Elliott Gould on the subway covered in blood is one of those stills always used to represent the film and with not a single word spoken it’s an amazing scene. The joke isn’t that no one notices, the joke is that they do and it’s one more thing that makes even more sense when seen now. Something very shocking happens in the film with still a half-hour to go that deliberately unmoors everything, leading to a payoff with the heavy breather on the phone that couldn’t be more perfect but the way it leads to the very end also makes the most sense for what the film wants to say, what it has to say. As well as what it wants to say about the very idea of things like apathy and cynicism, caring and feeling. How much the film knows what love is. And what to do with any emotion that comes from that.

The 35mm print of LITTLE MURDERS shown at the Egyptian to a sold out audience (it feels comforting how Bleak Week at the Cinematheque has become such a big deal) was worn but not faded and the rough feeling that it gave off always seemed appropriate so it played like a product of when it was made yet at the same time felt current and alive. No matter what anyone says, the antiseptic nature of digital projection will never contain as much life as this does. It made me react to the film. It made me feel connected to the film and emotional about everything that happened, no matter how absurd. And this was an amazing screening, likely one of the best I’ll attend all year. The film is funny, hysterically funny, brutally funny, with a packed audience that was laughing all the way through. Something about my mood that night caused me to not join in as much but deep inside I could feel myself responding to its power. It was as if I was feeling those laughs inside and this is going to remain one of my favorite screenings of this entire year. It just might be the true unsung and essential masterpiece of the early ‘70s.

This is also due to the remarkable performances from the entire cast. Elliott Gould starred in the original 1967 Broadway production which closed after seven performances. A more successful off-Broadway run directed by Arkin and starring others followed in 1969 that led to the film. Elliott Gould was basically the biggest star in the world in 1970 when this was filmed, recently Oscar nominated and on the cover of Time Magazine, and this is the film he helped to get made with that power. His performance is phenomenal, every bit of that apathy and confusion seen in his eyes and it’s maybe the most controlled of his early pre-LONG GOODBYE work. One long speech about having his mail opened by the government and what he did about this done in one unbroken shot is an unforgettable piece of work by him, forever haunted by what he learned about this person he never met. In addition to the fantastic extended cameos by Sutherland, Arkin and Jacobi, Marcia Rodd attacks her determination to find happiness with a ferocity that makes her continually endearing and always finds the right timing for the moment. As her family, Elizabeth Wilson (especially for the way she barks, “Language!” at Gould), Vincent Gardenia (especially for the way he answers the phone at one point by saying, “Hellooooo?”) and Jon Korkes (especially for when he makes that “woo, woo” sound after Alfred mentions the fancy magazines he works for) are all note perfect as are the great John Randolph and Doris Roberts as Alfred’s parents.

And Elliott Gould was there that night, arriving before the film in a wheelchair and viewing the film with him visible down front added an extra dimension to it for all those people in the packed house who would occasionally look over at him, watching him watch himself in the film. And he seemed emotionally overwhelmed during the wonderful post-film talk that followed with Larry Karaszewski, one of the best doing these things right now, covering all sorts of aspects of the film including the attempt to get Jean-Luc Godard to direct but it was the emotion of the event that night which has stuck with me more than anything. This was over a month ago as of this writing and I’m still thinking about how emotional it made me as well. And I’m thinking about how much this film means right now. “It is such a gift to be alive,” was the last thing Elliott Gould said at the end of the talk. This was a perfect thought for him to leave us with after the experience of this film. When a person like that says it, you believe him.

At the intersection where I live sometimes cars don’t stop for red lights. This is of course a problem considering how often I need to cross the street. But that’s what the world has become. “It's dangerous to challenge a system unless you're completely at peace with the thought that you're not going to miss it when it collapses,” is a line spoken by Elliott Gould in the film and it seemed to hang in the air that night at the Egyptian because it really does have an extra meaning right now. Every single laugh in LITTLE MURDERS is horrific. It’s an astonishing film and it makes perfect sense all these years after it was made, especially in this version of life we’re being forced to live through right now.